Large Cents (1793-1857)

1793 Flowing Hair “Chain” Cent

America’s first regular-issue cent debuted in 1793 with Liberty’s hair flowing on the obverse and a chain on the reverse meant to symbolize unity. The public panned it—newspapers said Liberty looked “in a fright,” and the chain read to many as bondage rather than union—so the Mint moved fast to redesign it. Struck only briefly in 1793, it’s scarce in any grade. Edge lettering reads ONE HUNDRED FOR A DOLLAR (incuse).

1793 Flowing Hair “Wreath” Cent

To defuse the backlash, the reverse chain was replaced by a wreath the same year. These cents still show the 1793 Flowing Hair portrait but pair it with a wreath reverse many found more dignified. Collectors prize the two edge types: the early Vine & Bars pattern and the later, incuse ONE HUNDRED FOR A DOLLAR lettering—both important diagnostics and fun variety hunting.

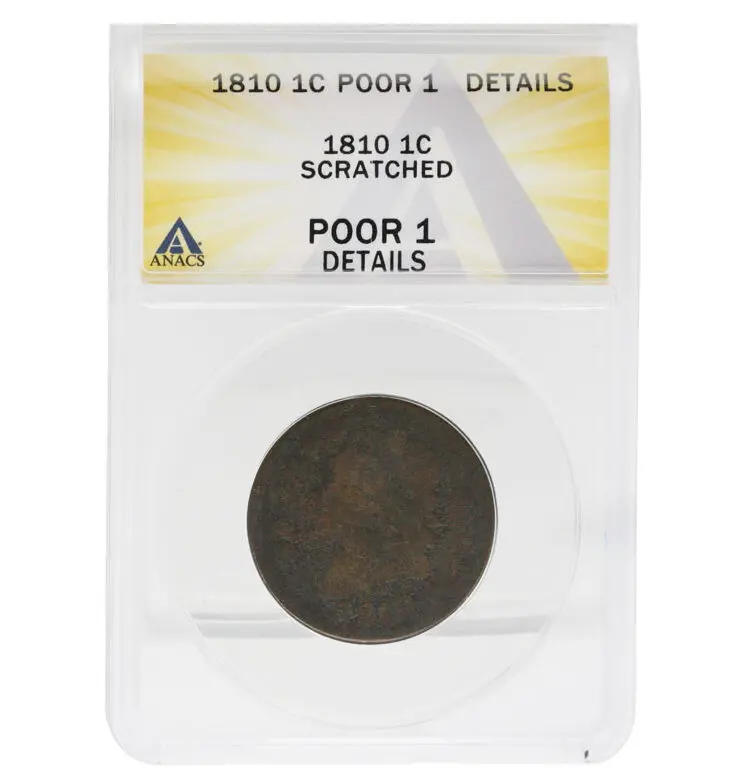

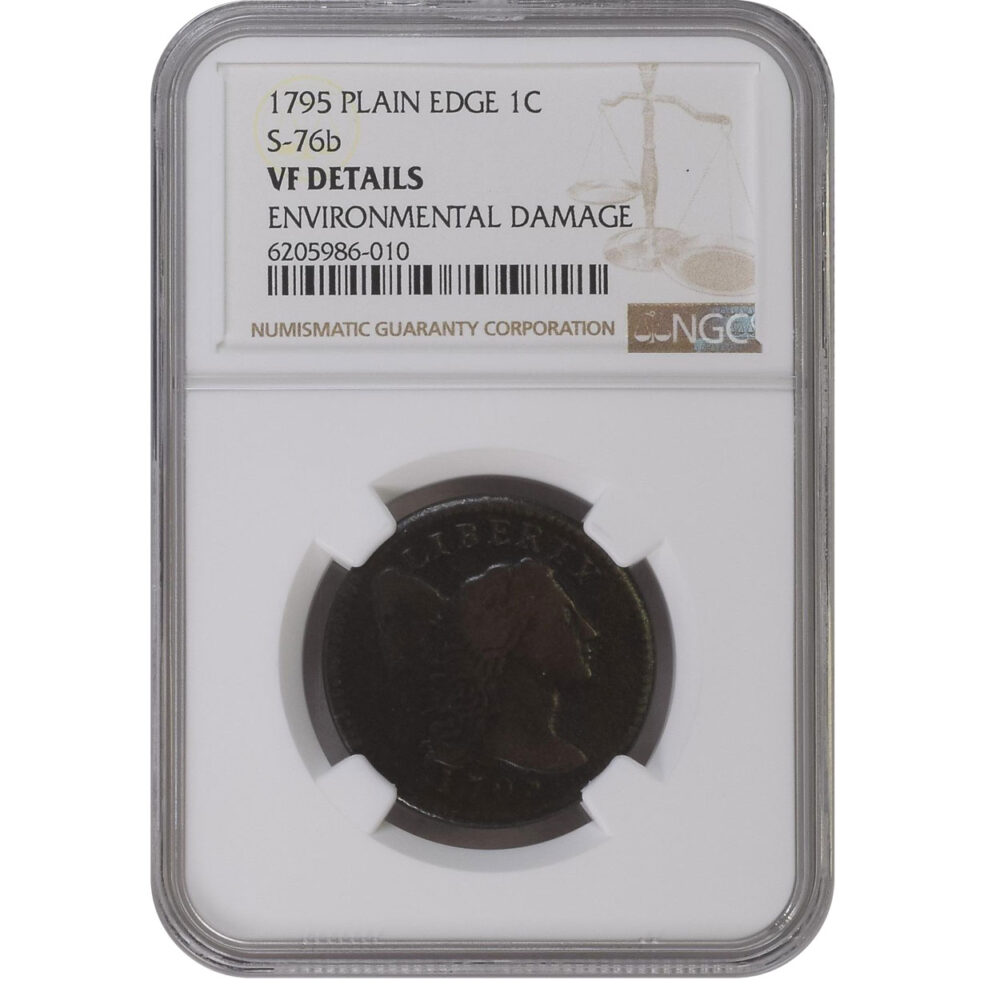

1793–1796 Liberty Cap

By late 1793 the Mint adopted Liberty Cap—Liberty now faces right with a pole and Phrygian cap, a classical symbol of freedom. Early pieces (1793–1794 and some 1795) still have lettered edges; later ones transition to plain edges. Look for the visual shift from a beaded border (1793) to denticles (1794–1796)—a quick way to sort dates and marriages. Ultra-rare 1795 reeded-edge pieces exist as celebrated anomalies.

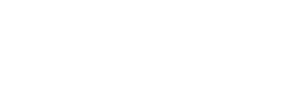

1796–1807 Draped Bust

Seeking a more refined national image, the Mint adopted Draped Bust—a portrait attributed to Gilbert Stuart, engraved by Robert Scot. Early issues keep the Small Eagle reverse (1796–1797) before switching to the Heraldic Eagle (1798–1807). Production quality stabilizes, edges are plain, and mintages rise versus the 1790s—but fully original, problem-free pieces remain challenging.

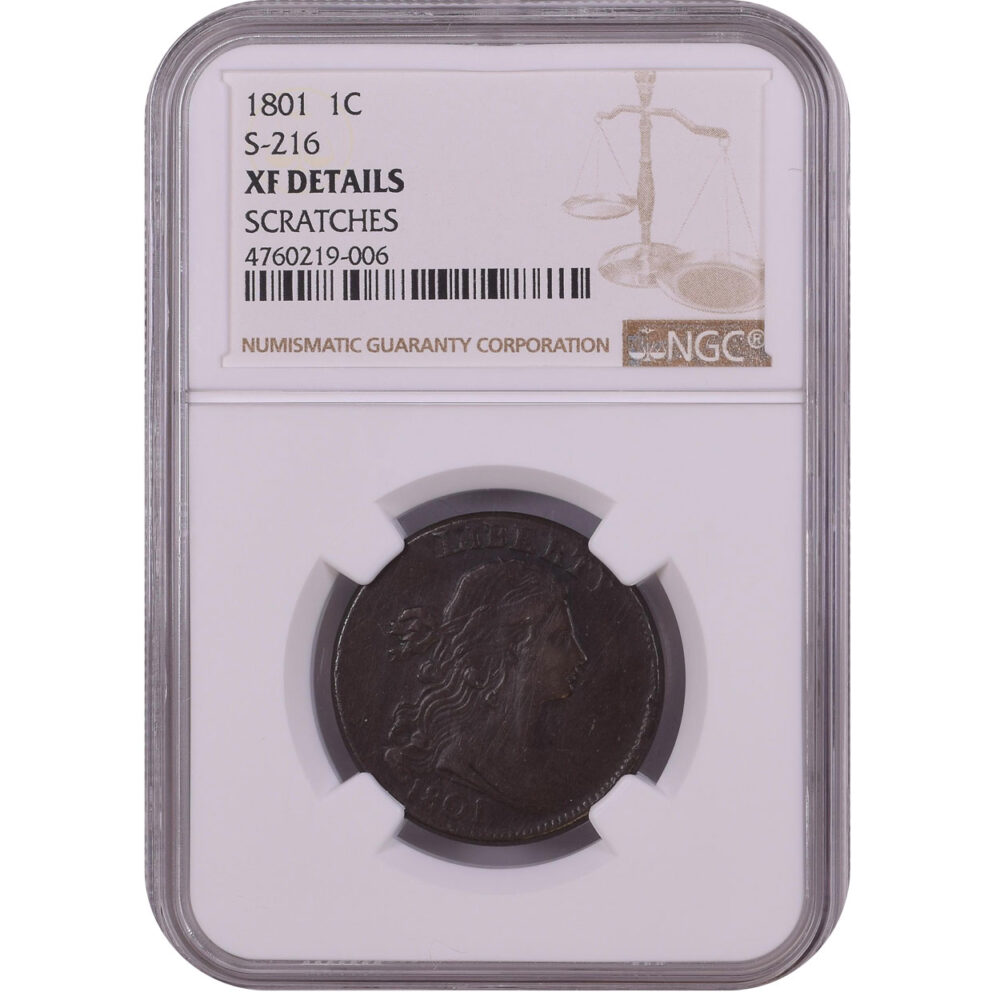

1808–1814 Classic Head

Under Robert Patterson, assistant engraver John Reich refreshed the cent with the Classic Head. Collectors quickly learn why nice ones are expensive: the era’s copper—softer/purer planchets—tended to wear and corrode faster, so truly problem-free coins are scarce. All have plain edges and rich die-variety interest. No cents are dated 1815; War of 1812 embargoes cut off planchet imports, and coinage resumed with 1816-dated dies. WikipediaStack’s BowersCoinWorldNumismatic News

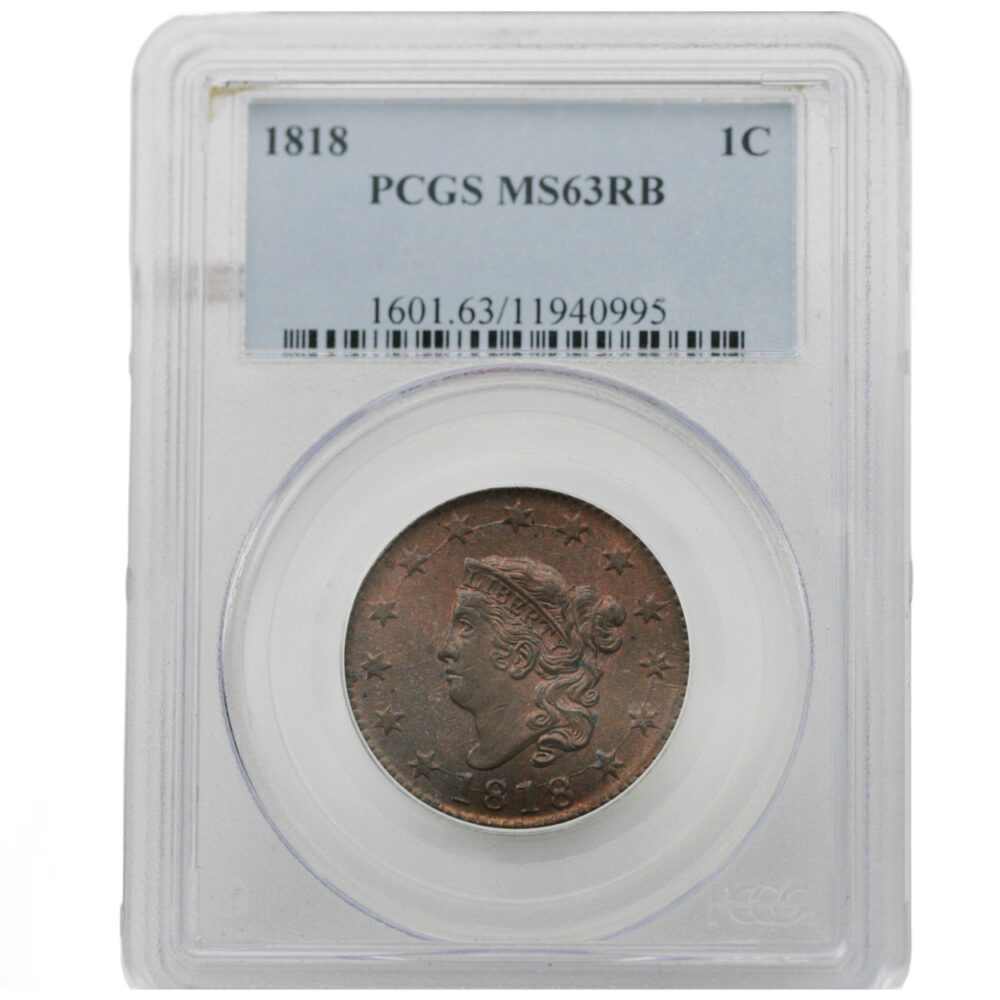

1816–1839 Coronet (Matron Head)

When planchets returned, the Mint introduced Matron Head (the first phase of the Coronet type). It’s a larger, more mature Liberty with many minor hub and date styles for variety specialists. In the 1830s, engraver Christian Gobrecht freshened the portrait (the “Modified Matron”) as mint technology improved—Philadelphia’s adoption of steam presses (1836) brought more uniform strikes and rims, setting up the final redesign to come.

1839–1857 Braided Hair

Gobrecht’s Braided Hair completed the evolution: a slimmer, youthful Liberty first seen as the 1839 “Petite Head,” refined again into the “Mature Head” (from 1843). Around this time the large cent’s diameter tightens from about 29 mm to ~27 mm, while remaining pure copper with plain edges—coins look more uniform thanks to modernized presses. Rising copper costs finally doomed the big cent; after 1857 it was replaced by the small Flying Eagle cent. A handful of unofficial large cents dated 1868 were struck later at the Mint and are collected as curiosities.

Why the Series Is Collectibly “Rare”

-

Short-lived early designs & tiny 1793 outputs mean low survivors today.

-

Planchet/press limitations (hand-powered through the 1820s) created many die marriages and striking quirks valued by specialists.

-

Classic Head metallurgy makes problem-free coins scarce.

-

Historical interruptions (War of 1812 → no 1815-dated cents) and evolving technology create natural collecting “chapters.”